Through the Myst: Creativity and Constraints

The bivouac recently came across this War Stories video by Ars Technica in which Rand Miller recounts how challenging it was to publish the seminal interactive title Myst. Launching such a beautifully immersive interactive experience was a remarkable feat in 1993. It required creatively navigating the technological constraints of early personal computers, reminding me of embracing the constraints of technology in my interactive work around that time.

Hyped Up On Hypercard

The bivouac had its own “war story” around the same time. The year was 1990. Apple’s HyperCard exposed many future interaction designers to the possibilities of interactive media. Simply placing invisible buttons anywhere over an image opened up creative avenues previously unavailable to storytellers and designers. Approachable and powerful, Bill Atkinson’s creation proved to be a friendly gateway to exploring code and non-linear interaction design for a wide range of designers in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

When clicked, these simple “go to” or “play” scripts were executed, taking users to other cards, flipping through a series of cards to create animations, or playing audio clips. Even though the experience was limited to simple black and white dithered images, Hypercard was its time's compelling and immersive platform with its unique combination of simplicity and creative publishing power. Indeed, hypercards preceded the commercial adoption of the World Wide Web and established the precedent of clicking on “hyperlinks” to navigate to additional information pages, which is commonplace using today’s web browsers.

Hypercard was a simple yet powerful introduction to interactive media for millions of users and designers.

A New Age of Interactive Multimedia

In the early 1990s, at the dawn of the age of interactive media, titles like “Columbus: Encounter, Discover, and Beyond,” produced by Robert Abel and distributed by IBM, set a new bar for empowering students to study a wide range of content in new ways. The title leveraged IBM’s large format IBM Ultimedia optical disc technology and was targeted at educational institutions.

The product description is impressive and reads:

“With James Earl Jones as narrator and Joe Morton as storyteller, these interactive titles span Europe and the Americas from the early Renaissance to the 20th Century from five different cultural perspectives -- White/European, Black/African, Hispanic/Latino, Asian and Native American. The largest multimedia project ever made, "Columbus," is on permanent display at the Library of Congress, National Demonstration Laboratories for new media and technology. Using an IBM CDROM drive, a Pioneer LaserDisc Player, and an advanced concept engine, "Columbus" connects 4400 scenes, 3,500 concepts, 5 hours of video, 180 hours of self-navigable imagery, and over 900,000 soft links on three videodiscs, and one computer optical disc.” This is a testament to the significance of the project.

As a budding interaction designer still in graduate school, I was so excited to see how the team was able to leverage visuals in icon form to help users navigate through the extensive content of the project. The possibilities of placing audio, visuals, and even early QuickTime film loops together, all to enhance storytelling, were influential to see in a commercial setting.

This and a piece focused on the immigration experience at Ellis Island created by Nancy Hechinger, who at the time had her multimedia production studio, Hands On Media. The Ellis Island work influenced my decision to explore using photorealistic points of contact within my interactive thesis work.

Exploring photorealistic points of contact was key to transcending interactive environments, which relied upon metaphor and abstracted icons. Abel’s work bridged the two worlds by providing vivid photos of objects or symbolic images, even on tiny button areas, guiding users across the environment’s functional elements. Hechniger’s work, and it is hoped that my thesis work also pushed the use of interactive elements further, allowing users to be further immersed in a story’s context.

Robert Abel and his team demonstrated the power of multimedia environments in educational contexts.

The Longest Day: An Interactive Thesis

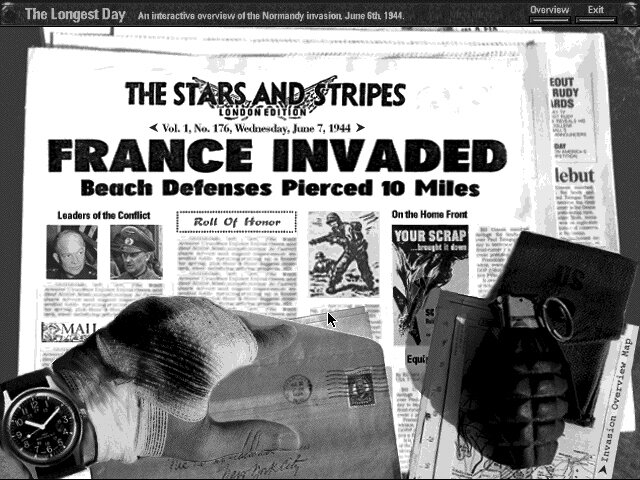

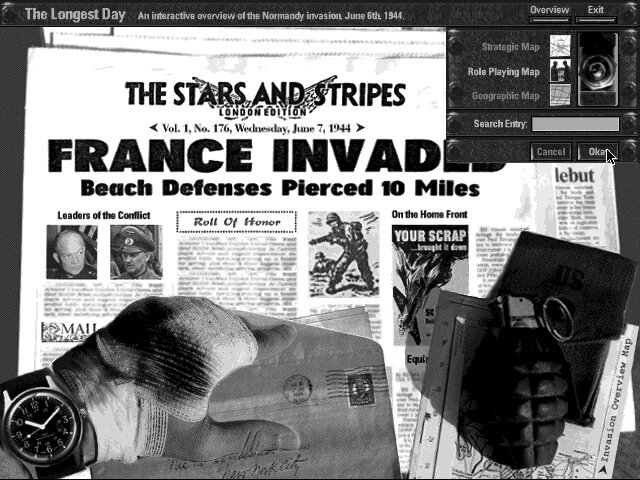

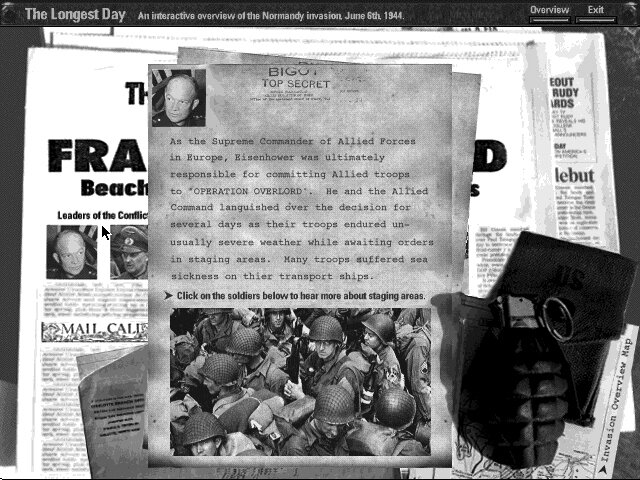

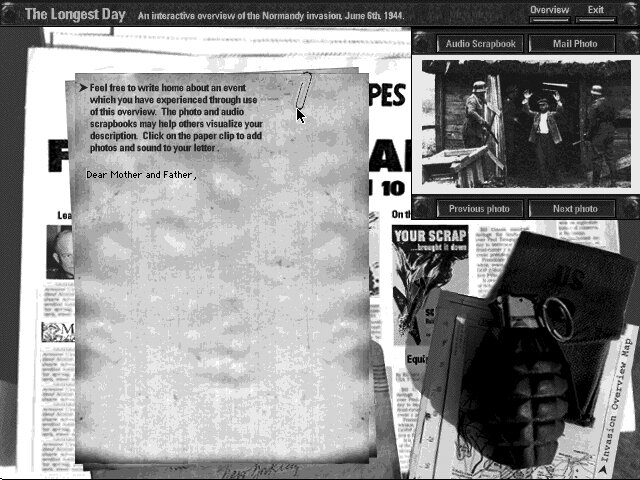

In 1992, as part of creating my thesis work, I explored the use of photorealistic interfaces to immerse users in content. Meredith Davis guided my thesis work at the College of Design at North Carolina State University. Meredith recognized the power of interactive technology early on, and she had deep expertise regarding pedagogy. My thesis project focused on how interactive educational environments could benefit abstract, concrete, active, and reflective learners.

Content focused on the Normandy invasion. Users could explore content using a photorealistic montage of objects common to the battlefields of World War II as an interface. Different days could be selected by clicking on arrows next to the date on the header of the Stars and Stripes newspaper. Content could be explored hourly by clicking on watch hands in the interface. Active learners developed empathy with leaders of the invasion by analyzing cause-and-effect scenarios using a role-playing map. Audio content from the film The Longest Day helped users understand what it must have been like to participate in the invasion. Finally, users could reflect upon their learnings and compose letters home that included audio and video clips from the film. In this way, creative writing skills could be assessed.

Just as with Rand Miller, though on a smaller scale, this thesis work involved overcoming serious technological constraints of the time. Created using Macintosh IIsi with 5MB of RAM and a 40MB hard drive, the Normandy invasion was chosen as a topic in part because the content lent itself well to a greyscale interface aesthetic. Most personal computers at the time were limited to displaying 256 colors, resulting in dithered images. However, computers could accommodate greyscale images acceptably. Similarly, the greyscale QuickTime film clips took less disk space and loaded faster. For further information on this thesis work and the golden dawn of the interactive media era, take a look at this Medium article I wrote a while back.

Upon completing graduate school, I took on a teaching position and, within a year, had shaped and was teaching some of the earliest interaction design courses of the early 1990’s. Working with various undergraduate and graduate students in programs ranging from communications design to painting and sculpture, new interactive media experiences were created with passion. Then, in 1993, Robyn and Rand Miller created Myst, raising the bar for what could be done with the interactive media. It inspired a new generation of interdisciplinary students and creatives to combine the power of computer programming, visualization, audio scapes, music, and storytelling in compelling new ways. Thanks to Rand Miller for sharing his war story and creating an inspirational example of how constraints invite creativity. And thanks for reminding the bivouac of its early 1990s “war story.”

The Longest Day: An Interactive Overview used intuitive photorealistic interaction points throughout the interface.

A Technological Footnote:

Created using Macintosh IIsi with 5MB of RAM and a 40MB hard drive, the Normandy invasion was chosen as a topic in part because the content lent itself well to a greyscale interface aesthetic. Most personal computers at the time were limited to displaying 256 colors, resulting in dithered images. However, computers could accommodate greyscale images acceptably. Hence, the choice to create the thesis in greyscale.